“Take care of yourself” is a slippery phrase. From one side of the glass, it says: self-care is important and good. It’s the underrated upswing in the churning productivity wheel. Enjoy the experience of being kind to yourself, it says, and hold onto the process of contributing generously to your own cause.

But flipped on its head, it's also a mandate: be careful of others, because you can't expect anyone else to offer you that kind of softness. Look out for number one: “Take care of YOUR self.”

There’s more than a whiff, of course, of feminised labour: watering a plant, keeping a child alive, taking a pet for a walk. But twist your head for yet another fly's eye angle: “I'll take care of it”, say Tony’s ultra-macho captains, on The Sopranos, when they are about to go and shoot someone to death.

All of which is to say that the task given by Sophie Calle to a selection of women in 2007 is one I would have relished “taking care of”. The piece, named for the final line in a letter sent to Calle by an ex-lover, involved the artist asking 107 women to interpret the missive’s meaning, in whichever way they saw fit.

Calle sees the piece as a way of "taking care of herself" in the aftermath of the breakup it precipitated, she explains in the text for its current online exhibition, at Galerie Perrotin, on until 19 July. The women she asks (who, it bears mentioning, in this show all appear to be white) often factor in their own professions as ways of responding. It’s a tip of the hat to the supposed certainty that comes with the authority of these roles.

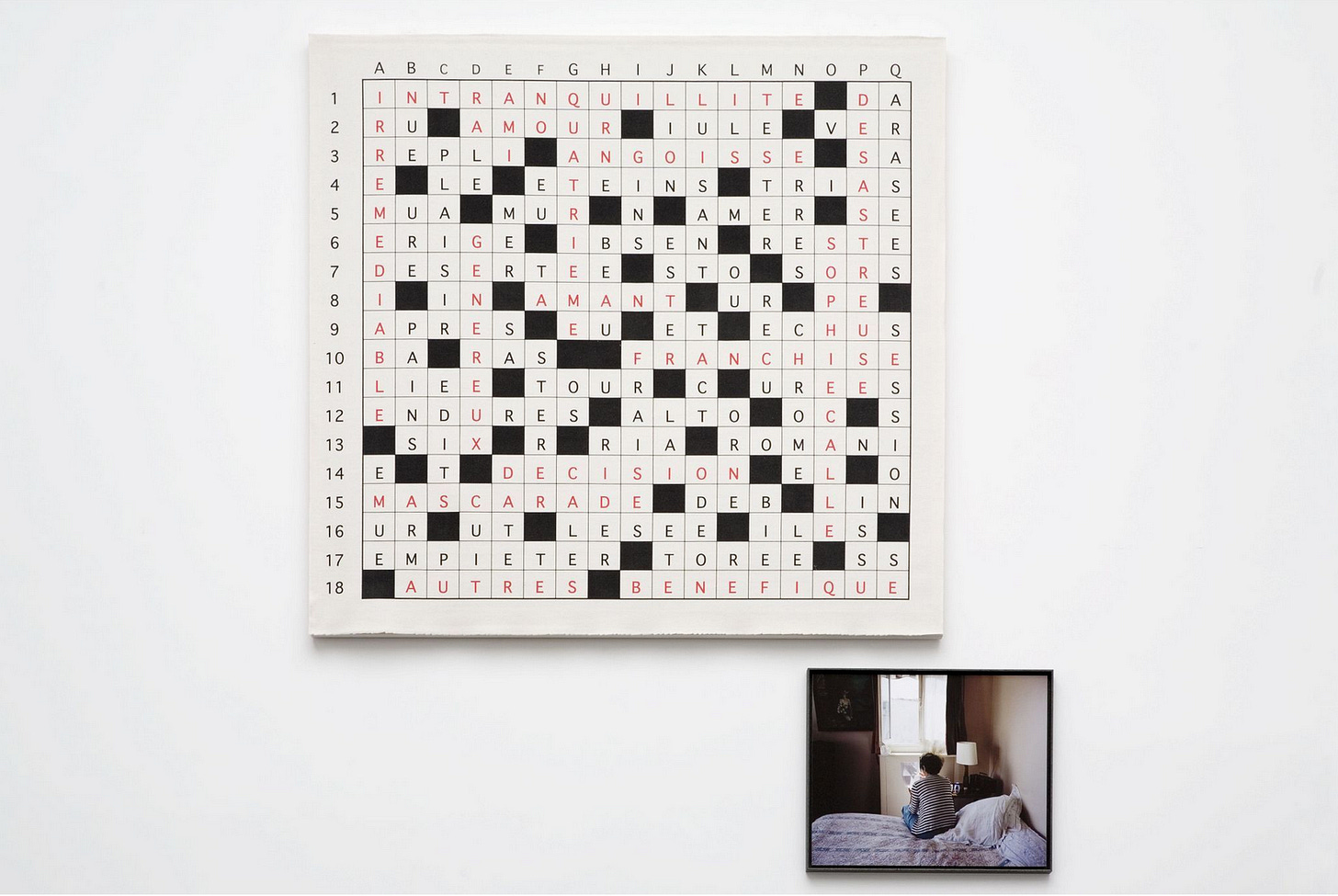

The accountant, for example, tallies up the number of active and passive tenses in the letter. The Latinist translates it ("Cura ut ualeas" is her reconfigured final line). The journalist explains why it can't be published in the newspaper ("The letter simply didn't kill anyone"). The crossword puzzle writer (French:"cruciverbiste”!!) turns the words into a grid of interlocking concepts, conjunctions, adverbs and thoughts, many of which need no translation: Irremediable. Destastreuse. Amour. A nine-year-old schoolgirl writes in the most frankly devastating appraisal of the letter, as if composing a book report - "He writes to tell her that he would like to break up…She is nice but she is complicated.” The letter itself is nowhere to be found.

Calle picks the people she wants to respond to the letter, enacting the sent screenshot, the request for a second opinion. "AIBU" (Am I being unreasonable?) asked the mums, day after day, when I worked on a parenting forum. On Reddit: it’s “AITA” (am I the asshole), where the internet doubts our capacity to ascertain our own assholery. Calle too, doubted, and in the hands of her art practice (which here, as so often, slips into a similar forensic obsession that I Love Dick relishes), the letter becomes an opportunity to build something out of the digging of questions.

Tinder, facebook, whatsapp, text: the quotability of a screenshot means we now receive endless snippets of conversation for appraisal. Just a second opinion, before a wrong step is taken - a creep we need to be assured is actually saying what we think he is, a date we shouldn’t plan, an apology we should rethink. Words don’t need to be paraphrased, on the internet, and can instead be delivered exactly as "spoken" to the analyser. They can be passed on, meticulously and line-by-line, and are expected to convey the whole weight of context where that conversation lives.

We hope that passing on our screenshots will excavate something we can’t."He hates me", my friend commented, for example, messaging me a screenshot showing a man saying that he, too, had a good time last night. "HE DOES NOT HATE YOU", I wrote back. But the complete impossibility of a definitive answer on these issues is why Calle’s piece works so well: none of these women can give her what she wants. As a series, they only reinforce the loneliness of interpretation, the solo effort of working it all out.

Behind the scenes

In a year when I've done more video calling than ever before, the one I did for this roundtable was my favourite. Five incredibly funny woman, who weren’t friends when we began, talking about the stuff they cared the most about. Which, often, was labour. Why some is valued, and some isn't. Why some people get paid and some don't: what being a woman has to do with it all. In retrospect, I wish I'd talked more about how race affects those things too. I also wish I’d been able to wax on about some of my favourite hits these comedians have done (in particular: Alyssa Limperis as a British influencer has pulled me out of some dark dark days this year.)

What has made me feel great pride and affection in this piece is something not journalistic at all: how much all these comedians hit it off! It became clear in the final rounds of fact-checking that they were all groupchatting as I was talking to them (At first: weird! But once I thought about: incredibly cool), and there are constant jokes pinging between them all on Twitter. I guess I love to be a friend matchmaker? A socially distant COVID need I didn’t even know I was missing.

I’m into:

I just gobbled up a run of Ursula K. Leguin novels, including The Dispossessed, which somehow feels incredibly of-the-moment (themes: science, politics and how those affect the wellbeing of society), despite being written in 1975.

An update!

I switched to Substack! I hope it works OK, please let me know if there are teething issues!

Josie xxx